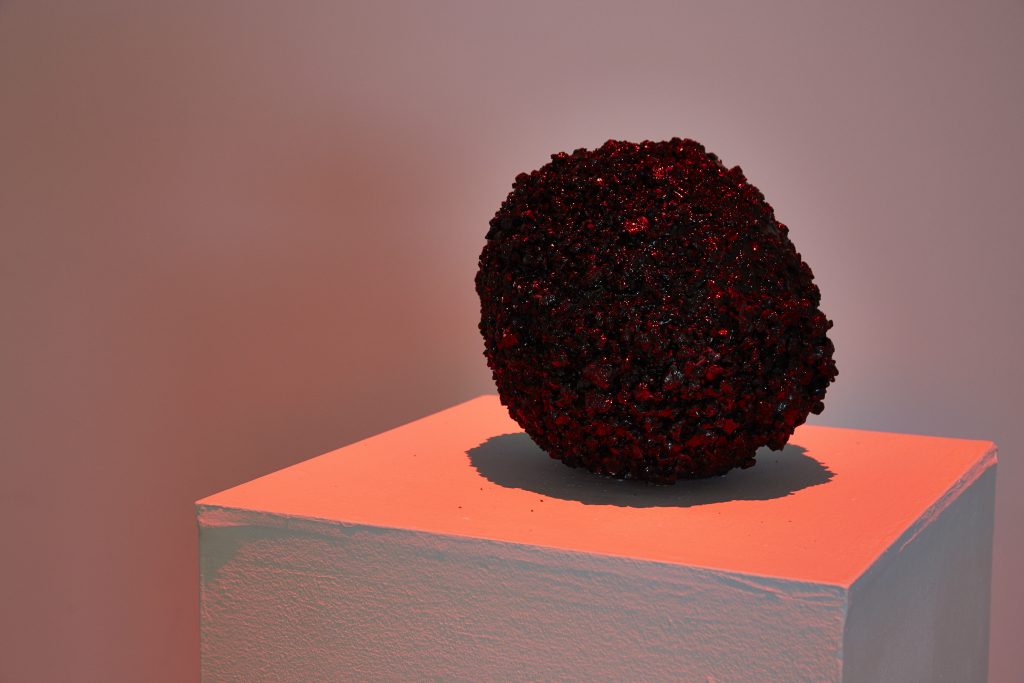

Image courtesy of Kathryn Maguire

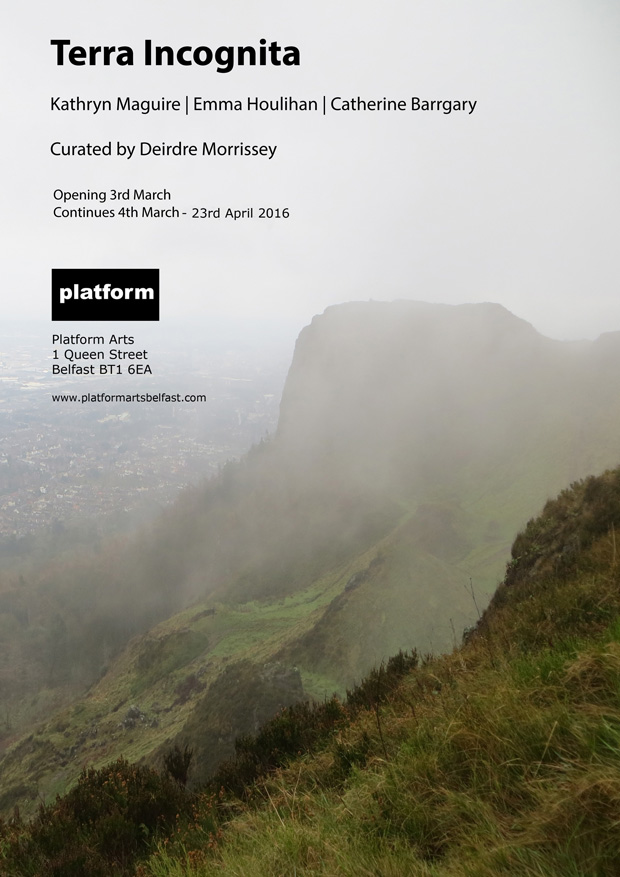

Catherine Barrgary | Emma Houlihan | Kathryn Maguire

Curated by Deirdre Morrissey

4th-23rd March 2016

Opening 6pm, Thursday 3rd March

Gallery 1

Terra Incognita is a Latin term used by early cartographers referring to un-colonized or unconquered land, or what was often referred to as virgin territory. The word ‘incognita’ here is the female of the term ‘incognito’ where ones identity is concealed or hidden. The feminization of hidden, unknown or unconquered land even the feminization of the word ‘virginal’ reminds us of the male perspective on the language used to refer to possession and territory. Land was considered virgin territory if untouched but land could also be raped and plundered through conquest, as could the female body.

Ownership of land historically was considered a male right of possession, so perhaps the land itself was considered female in order to be the counterpoint of the male farmer. The term Terra Incognita is used when referring more specifically to land as property. The concept of land as personal property is said to have come about with the advent of the agricultural revolution and with agriculture came a need to control personal territory. Inequality amongst the sexes is said to have its roots in the social organisation of the farming societies when women also began to be considered part of a man’s property and their status declined.

So if land is not owned, named or farmed it becomes Terra Incognita – it is left unchartered, a blank space on an old map. In many ways the same could be said historically of women; if they were not married (owned and named) or farmed (childless) then they did not hold status in the community. Like the untouched woman these blanks on colonial maps held a sort of mystery, a place yet to be explored or controlled. The desire for control of territory through colonization meant that these unexplored places eventually diminished and so Terra Incognita can also serve as a reminder of the tenuousness of possession of land.

The three female artists chosen for this exhibition Terra Incognita have all responded individually to these ideas. Their artwork broadly references the land, geography, its physical material make up and also wider philosophical notions about inhabiting unchartered spaces and exploration. Each artist possesses an intuitive response to materials in their individual art practices and a sensitivity to common notions of territory and possession.

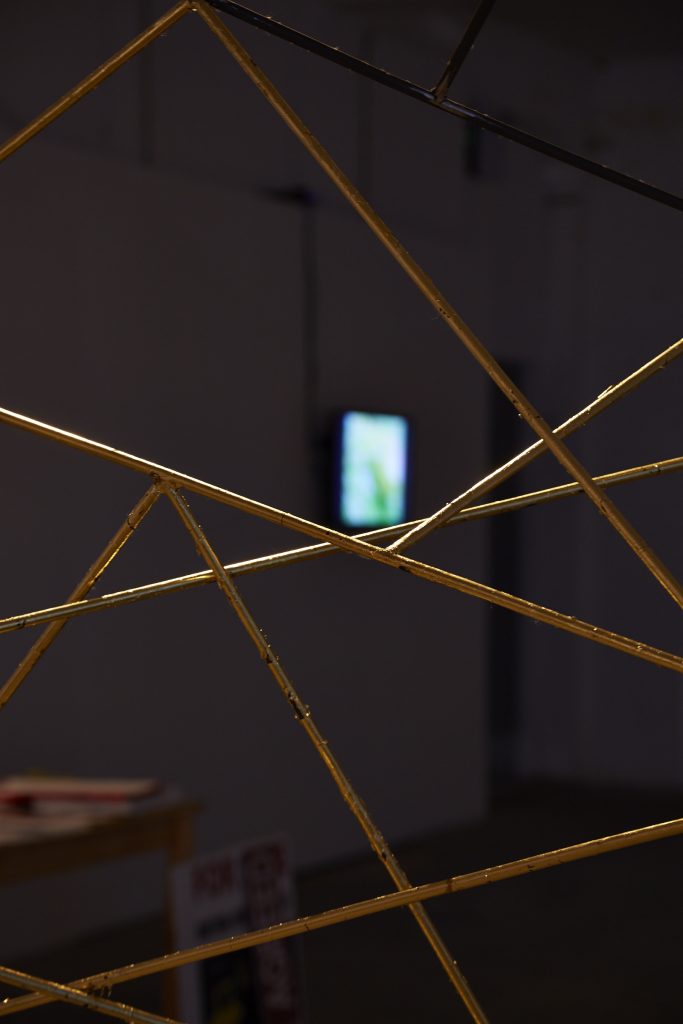

EMMA HOULIHAN

Co Clare

Emma Houlihan fluctuates between protagonist and antagonist, reading the landscape and its potential for transformation. A series of actions exist within the public sphere and the gallery, interactions and interventions which crystalize the incidental moment in an expanding process of enquiry.

KATHRYN MAGUIRE

Dublin

Kathryn Maguire’s practice uses text, sculpture, video, and installation work. She has used text and materials of signage as a means to highlight historical writings in public spaces, making diverse cultural references that link the historical with contemporary. She seeks to highlight moments from history, looking in the past for a potentiality, which represents an opening and a questioning. In a new departure Maguire explores the idea of Time and is currently researching geological events throughout the history of time and deep time.

CATHERINE BARRGARY

Dublin

In her practice Catherine Barrgary generates sculpture, performance and immersive events. These are lightly held or fused together using humble and often reversible processes. The outcomes of these processes are fragile and contingent, so that the work emits a vulnerable human presence. This gives sense that the work has been made by an outsider, encountering and repurposing human knowledge and materiality. She uses art as a form of poetic politics.