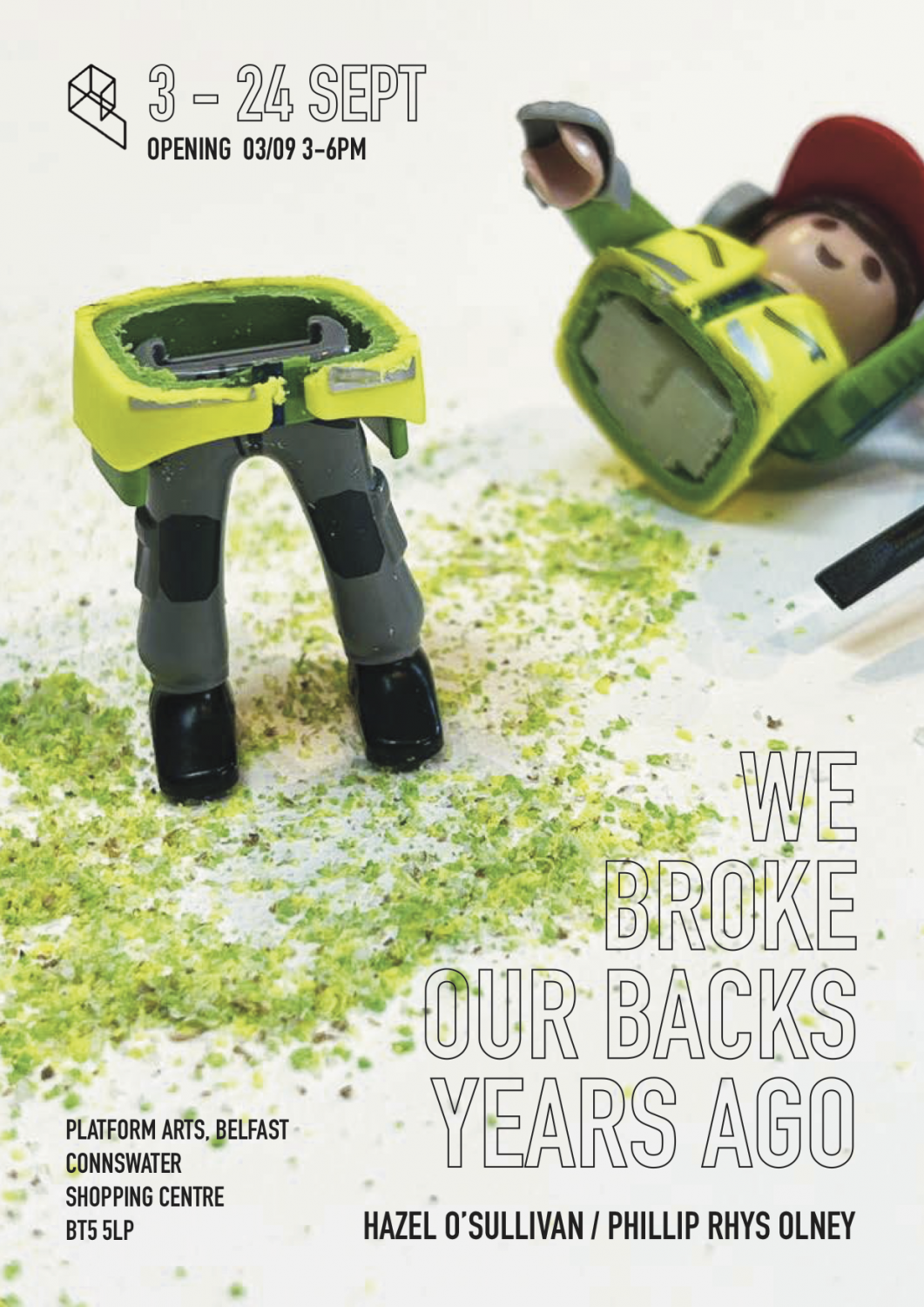

WE BROKE OUR BACKS YEARS AGO

3rd – 24th September 2022 Platform Arts, Belfast

Hazel O’Sullivan and Phillip Rhys Olney present a collaborative show at Platform Arts, exploring so- cial-class and personal heritage with specific reference to labour and the home. Spaces once occupied and operated by those dependent upon its employment are transforming into corporate shells, managed and orchestrated by governing bodies which lack the experience of the labour they supervise. Linked by their shared heritage from within these communities, both artists contend that we are losing the vast wealth of human experience, knowledge and taste which has laid the foundations for these trade sectors and their co- inciding lived-in spaces. Phillip’s direct lineage – hailing from a line of stevedores, unskilled labourers and mechanics – compliments the socially conscious and domestic aspects of Hazel’s practice.

Both artists view the harsh uniformity of corporatisation – of globalisation, capitalism, containerisation and gentrification – as a threat toward those men and women upon whom these traditional industries have histor- ically depended. Both artists document, preserve and in doing so investigate the current disintegration and disregard for the labour, toil and industry of the people which built and sustain these communities.

In Hazel’s practice, conditions of livelihood and political housing queries translate to sculptural forms that explore class-taste. Minimalism and often Formalism offer a detached narrative for Hazel to explore her work, approaching Irish housing politics with a personal sense of disillusionment and detachment from the idea of ‘home’. Transposing a sense of containment metaphorically upon the societies around the docklands, Hazel’s two sculptures address the impact of architectural and corporate privatisation on our communities. Combining a strong critique on Le Corbusier’s housing project ‘Unité d’Habitation’ with the redundant cranes present at each dockyard, intentionally secluded domestic forms reflect the impact of generational redundancy and the role architecture plays within modern gentrification. Static yet shifting forms seek to address the role of containerisation in labour force reductions across Dublin, Southampton and Belfast Docklands, as seen in Hazel’s architectural painting. With the industrial material of wood stain applied toplywood, this three-part composition articulates a sense of social constraint present within both historical and contemporary working-class societies, a constraint produced by housing and workforce inequalities.

Inter-generational labour lies at the heart of Phillip Rhys Olney’s practice. He investigates the role of work amid the cultural contexts of class, education and social mobility. Hailing from three generations of dockyard workers, Phillip’s work explores his ancestry through a continued dialogue between him and his father. This is perhaps best seen in CCTV footage, immortalising his father’s 2008 crane crash. Phillip uses materials typically found in industrially-coded locations: scaffolding boards, ratchet straps, concrete, steel and tarpaulin. In doing so, his multimedia practice explores the contemporary roles and relevance of sites of traditional working industries. These include more intimate, personal locales such as Southampton Dock- yards alongside those more broadly across Britain, and ask to what degree do these sites collude to form a typically ‘masculine’ national ‘British’ identity.

Creating an arresting dialogue between the politics implicit in labour, corporatization and social mobility, the two artists use the ‘arena’ of dockyard spaces to discuss the experience and ‘shift’ of social mobility more broadly. Nevertheless, as two voices crucially distant from the tough physicality of the industries they come from, the artist’s collaboration preempts another critical ‘turn’. As descendants of a working-class heritage, where does this generation of artists, born into a hard-earned comfortability, fit?